Edited by Alexandra Bindon

_____________________________________________________

III. Important Artists and Their Works

VI. Additional Resources

_________________________________________________________

What is surrealism? What does it mean for a work of art to be surreal? Surrealism works are, in some ways, similar to mixed metaphors that create a new meaning. A surrealist fuses two or more images together to create an impossible reality encompassing several distinctly separate worlds (Clancy 273). Drawing heavily from the Dadaist movement, Andre Breton (1896-1966) formed the movement and wrote his first Manifesto of Surrealism in 1924 (Clancy 272). In it, he defines surrealism as "pure psychic automatism, by which it is intended to express, verbally, in writing, or by other means, the real process of thought . . . in the absence of all control exercised by the reason and outside all aesthetic or moral preoccupations . . . [and] rests in the belief in the superior reality of certain forms of association neglected heretofore; in the omnipotence of the dream and in the disinterested play of thought" (Breton). This type of surrealism defines Veristic/Illusionist Surrealism, who believed that their works, as images linking spiritual realities and the physical world, stood as metaphors to inner truth.

Automatist Surrealism: "Agony" by Arshile Gorky Veristic Surrealism:"The Elephants" by

Veristic Surrealism:"The Elephants" by

They believed in analyzing surrealist works to find the metaphors, and, by understanding these metaphors, they believed they could understand the world around them. They are similar to the automatists in that the metaphors found in mixed images are expressions of the subconscious, except they then analyzed these images to discover meaning (Sanchez). The second type, Automatist Surrealism, is based off of the "free association" concept, using abstraction to portray emotions and create a mood. The automatists, directly from Dadaism and from automatic writing (“20th Century Art History”), rebelled against the idea of form in favor of abstraction (Sanchez). They wanted to bring the subconscious to life by expressing feelings in their art, with understanding coming not from analysis but from immediate recognition.

Veristic Surrealism can be seen as a different form of finding connections amidst fragmentation, comparable to what T. S. Eliot and other modernist writers attempted to show.  Veristic artists put dissimilar images and realities into one work of art that the audience analyzes the connections, hopefully arriving at a better understanding or realization of truth. In "The Waste Land," Eliot does similarly by using different myths, religions, locations, characters, languages, scenes, and on, "uniting disparate objects and experiences through metaphor," forcing the reader to analyze and make the connections (Skaff 133). Eliot also bases his philosophies of religion and of art off his concept of the unconscious, as do surrealists, so "the extent to which Eliot's poetry resembles Surrealist art, then, depends upon the

Veristic artists put dissimilar images and realities into one work of art that the audience analyzes the connections, hopefully arriving at a better understanding or realization of truth. In "The Waste Land," Eliot does similarly by using different myths, religions, locations, characters, languages, scenes, and on, "uniting disparate objects and experiences through metaphor," forcing the reader to analyze and make the connections (Skaff 133). Eliot also bases his philosophies of religion and of art off his concept of the unconscious, as do surrealists, so "the extent to which Eliot's poetry resembles Surrealist art, then, depends upon the  extent to which Eliot's and the Surrealists' theory of the unconscious and its role in artistic creation coincide" (Skaff 133). Eliot, though, was never affiliated with the Surrealist Movement, and is not specifically a Surrealist, sine he did not subscribe to the political and ethical dimensions of Surrealism. His art, though, does have quite a bit of overlap in artistic theory and is therefore "generically surrealist, beyond the point of merely sharing certain resemblances" (Skaff 132).

extent to which Eliot's and the Surrealists' theory of the unconscious and its role in artistic creation coincide" (Skaff 133). Eliot, though, was never affiliated with the Surrealist Movement, and is not specifically a Surrealist, sine he did not subscribe to the political and ethical dimensions of Surrealism. His art, though, does have quite a bit of overlap in artistic theory and is therefore "generically surrealist, beyond the point of merely sharing certain resemblances" (Skaff 132).

Different venues displayed Surrealism, usually little magazines and art exhibits. Official surrealist magazines were mostly in Europe, including the French Minotaure and La Révolution Surrealiste. Famous art exhibits took place in the Pierre Colle and Gradiva galleries in Paris, and there were several international exhibits (King). A different venue, although minimally used, is the novel, despite its being discredited by Breton (Matthews 2). Also, it was a prominent technique implemented by artists affiliated with the avant-garde movement.

Surrealism is larger than little magazines and art exhibits, found in many different fields because it is “a point of view in all these fields more than it is a movement;" these fields include literature, art, psychology, philosophy, politics, and so forth (Clancy 271). In politics, the ideas of Karl Marx attract many surrealists, and in psychology, the ideas of Freud appeal to them (Clancy 273). Surrealism actually uses psychoanalytic ideas, especially the idea that "the unconcious held universal imagery" (“20th Century Art History”).

Surrealism, according to Keith Eggener, arrived in

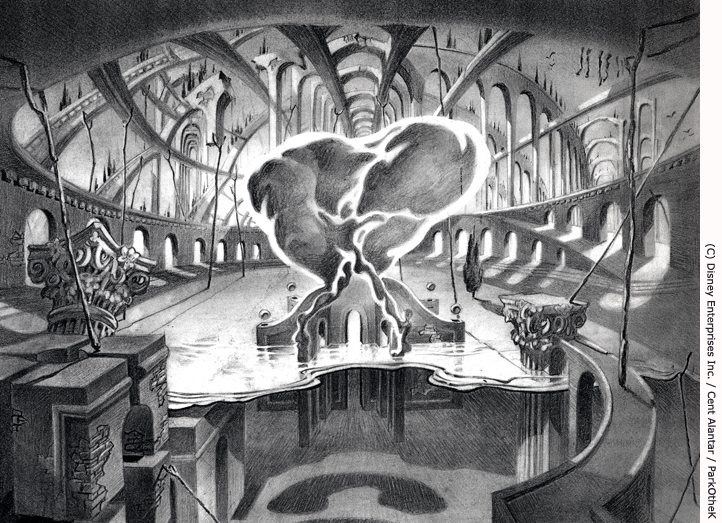

Destino Disney animates Dali's works (began 1846, finished 2003)

Surrealism in the U.S. was strong in the 1930s-1950s, especially in the 1940s when many European surrealists moved to New York, including the founder Breton, to escape World War II; after WWII, most went back home to Europe. Many American surrealists did not officially joined the movement, preferring to experiment on their own, creating new artistic movements ("Surrealism USA").

Identifying American artists influenced by surrealism who are not actual surrealists artists is difficult. The term "American Superrealism" refers to those artists--born, raised, and living in America--who exploited "the ciritical possibilities of European surrealism" before the European artists themselves came to America (Veitch 15). Jonathan Veitch lists several American artists who used ideas from Dadaism and Surrealism: "Many Ray, Joseph Stella, Charles Demuth, Peter Blume, Morton Schamberg, Djuna Barnes, the Arensberg circle, Wallace Stevens, Mina Loy, Charles Henri Ford, William Carlos Williams . . . [and] Nathanael West" (xviii). Charles Henri Ford, who thought of himself as a surrealist, began a little magazine in America called View, which showcased American artists--such as Wallace Stevens, William Carlos Williams, Henry Miller, and Paul Bowles--as well as European ones.

View was never officially a strict Surrealist little magazine, as he published artists completely unassociated with Surrealism, because he did not want View to be "an obscure avant-garde magazine" (Otwell). Even so, View "did launch and sponsor the Surrealists in America" (Otwell). And when Andre Breton first came to America in 1941, he worked with Ford to produce two purely Surrealist publications of View. However, Ford did not allow Breton to control View, but instead broke with him and affirmed American Surrealism as distinct from European Surrealism. A turning point came in the article "Americana Fantastica," which critiqued Breton's "logic of generation" and "methodologies of the fantastic" in favor of the irrational plus architecture or organization (Otwell).

III. Important Artists and Their Works

European Writers/Poets:

Philippe Soupault

J. K. Huysmans

Raymond Roussel

Rene Crevel

Robert Desnos

Julien Gracq

Joyce Mansour

Gisele Prassinos

Andre Pieyre de Mandiargues

"Woman in love" ("L'Amoureuse") by Paul Eluard

She is standing on my eyelids

And her hair is in mine,

She has the shape of my hands,

She has the color of my eyes,

She is swallowed in my shade,

Like a stone against the sky.

She will never close her eyes

And will never let me sleep;

Her dreams in day's full light

Make suns evaporate,

Make me laugh and cry and laugh,

Speak having nothing to say.

American Writers/Poets:

James Johnson Sweeney

Harold Rosenberg

"There is this distance between me and what I see" by Philip Lamantia

There is this distance between me and what I see

everywhere immanence of the presence of God

no more ekstasis

a cool head

watch watch watch

I'm here

He's over there ... It's an ocean ...

Sometimes I can't think of it, I fail, fall

This IS the book of love

there IS the Tower of David

there IS the throne of wisdom

there IS this silent but a lot

Constant flight and air of the Holy Ghost

I long for the luminous darkness of God

I long for the superessential light of this darkness

Another darkness I long for the end of longing

I long for the

it is nameless what I long for

a spoken word caught in its own meat saying nothing

This nothing ravishes beyond ravishing

There IS this book of love Thrown Silent look of Love

European Artists (although many lived in America for some part of the time):

Rene Magritte

Pierre Roy

"Indefinite Divisibility" by Yves Tanguy "The Louis XVI Armchair" by Andre Masson

"Hector and Andromache" by Giorgio De Chirico

American Artists:

Dorothea Tanning Gerome Kamrowski

Alexander Calder Jackson Pollock

Joseph Cornell Knud Merrild

James Guy Alexander Calder

Walter Quirt Robert Motherwell

Isamu Noguchi Walt Disney

"Danger, Construction Ahead" by Kay Sage

"A Little Night Music" by Dorothea Tanning "South of Scranton" by Peter Blume

.jpg)

"The Moon-Woman Cuts the Circle" "Sea Phantoms" by William Baziotes

by Jackson Pollock

"Mental Geography" by Louis Guglielmi

"Venus on Sixth Avenue" by James Guy "Salvation" by Walter Quirt

"The Circus" by Alexander Calder "Untitled (Cocatoo and Corks)" by Joseph Cornell

"Humpty Dumpty" by Isamu Nogichi

Surrealism was declared dead in 1941 (Sanchez), as after World War II, most exiled artists returned to their homes and Surrealism galleries closed down. Surrealism affected the artistic world, as several movements either came directly out of or were influenced by it: Abstract Expressionism, Social Surrealism, California Post-Surrealism (1934 and onward), Magic Realism, Automatism, and Deep Image Poetry ("Surrealism USA"). The surrealist movement has not completely died, though, for as technology has made digital art possible, a new generation of digital artists, either Neosurrealists or Modern Surrealists, pursue surrealist aims ("Neosurrealism").

“20th Century Art History.” Words of Art. Pixiport. 4 Apr. 2007. <http://www.pixiport.com/words-art-20th-centuryart.htm>

“Art History: Surrealism: (1924 – 1955).” World Wide Web Arts Resources absolutearts.com. 5 Feb. 2006. World Wide Web Arts Resources. 26 Apr. 2007. <http://wwar.com/masters/movements/surrealism.html>

Breton, Andre. “What is Surrealism?” Public meeting. Belgian Surrealists.

Clancy, Robert. “Surrealism and Freedom.” American Journal of Economics and Sociology 1949. JSTOR.

Eggener, Keith L. “‘An Amusing Lack of Logic’: Surrealism and Popular Entertainment.”

“Grant Hanna.” Ferner Galleries. 2006. Ferner Galleries. 26 Apr. 2007. <http://www.fernergalleries.co.nz/default,44.sm>

King, Stephen D. "A History of Surrealism." Surrealist.com. 1998. Surrealist.com. 26 Apr. 2007. <http://www.surrealist.com/history.aspx>

Matthews, J. H. Surrealism and the Novel. Michigan: U of Michigan, 1966.

"Neosurrealism." Answers.com. 2007. Answers Corporation. 27 Apr. 2007. <http://www.answers.com/topic/neosurrealism>

Otwell, Andrew. "American Surrealism and View Magazine." Andrew Otwell. 1996. Creative Commons. 26 Apr. 2007. ,http://www.heyotwell.com/work/arthistory/view.html>

Sanchez, Monica. "History of Surrealism." Monica Sanchez. Monica Sanchez. 4 Apr. 2007. <http://www.gosurreal.com/history.htm>

Skaff, William. The Philosophy of T. S. Eliot: From Skepticism to a Surrealist Poetic. Philadelphia: U of Penn P. 1986.

"Surrealism USA." Surrealism USA. 8 May 2005. Traditional Fine Arts Organization, Inc. 4 Apr. 2007. <http://www.tfaoi.com/aa/5aa/5aa249.htm>

Veitch, Jonathan. American Superrealism: Nathanael West and the Politics of Representation in the 1930s. Madison: U of Wisconsin P, 1997.

VI. Additional Resources

"Surrealist Art." http://www.cnac-gp.fr/education/ressources/ENS-Surrealistart-EN/ENS-Surrealistart-EN.htm

"Dada and Surrealism." http://www.seaboarcreations.com/sindex/veristic.htm

"Surrealism Research Index." http://www.seaboarcreations.com/sindex/

"The Surrealist Movement in the USA." http://www.surrealistmovement-usa.org/

"The Salvador Dali Gallery." http://www.daligallery.com/

"Surrealism." http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/surr/hd_surr.htm

"Taken from Franklin Rosemont's Introduction to André Breton's volume of selected writings entitled:What is Surrealism?"

<http://www.studiocleo.com/librarie/breton/bretonbiography.html>

Neosurrealism Art and Modern Surrealism Art. http://www.neosurrealismart.com/3d-artist-gallery/index.htm

Link back to Encyclopedia of Modern American Literature